Spirit Rock I

Study OverviewIn this study, we collaborated with Spirit Rock Meditation Center to test whether a month-long, Insight meditation retreat would improve practitioners’ ability to flexibly maintain and apply their attention during the performance of complex cognitive and emotional tasks. We formulated a battery of six behavioral tasks that retreatants performed onsite at the beginning and end of their one-month retreat. We designed the study to be self-sufficient as practitioners were in silence. We used a control group roughly matched on meditation experience drawn from the Spirit Rock community who performed the tasks onsite at Spirit Rock and in silence.

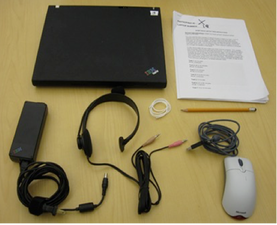

Intervention: Insight meditation is a form of vipassana meditation rooted in the Theravada tradition. Core practices include mindfulness of breathing and redirecting one's focus to present moment-experience. Participants also received instruction in ancillary practices intended to cultivate aspirational qualities known as the four immeasurables: loving kindness, compassion, empathetic joy, and equanimity. Silent, residential retreats are designed to support continual practice throughout the day, and include up to 10 hours of practice alternating between sitting and walking meditation in 30-45 minute intervals, meals, and an hour of work meditation, such as housekeeping or kitchen duties. Participants: We recruited 30 people (age range 25-70) who were participating in one of the two annual month-long vipassana (insight) meditation retreats at Spirit Rock Meditation Center in Woodacre, California. A second group of individuals (23-72 yrs.), serving as a control group, were recruited from the local Spirit Rock community. The control group had previous experience with meditation but did not undergo intensive meditation training during the study. Procedure: Before and after the meditation retreat, each participant set up their room as a testing environment (controlled lighting, standardized position relative to a provided laptop) and completed cognition- and emotion-related tasks per paper and onscreen instructions. The setup was designed to be compatible with individuals engaged in noble silence and generally did not require any direct communication with the research team while on retreat. Six tasks were administered as described below. In addition, participants were required to fill out a battery of self-report questionnaires within 48 hrs of their completion of the laptop tasks. The control group underwent the same testing process by traveling to Spirit Rock, where they engaged in a self-guided short meditation session to settle upon arrival and then walked to the same dorm rooms the retreatants stayed in and used for their testing sessions. As with the retreatants, the control participants received a laptop kit at their rooms and set up the testing environment as per paper and onscreen instructions. |

Research TeamPrincipal Investigator:

Clifford Saron, PhD Trainees: Brandon King, MA Anthony Zanesco, PhD Katherine MacLean, PhD Stephen Aichele, PhD FundingThis study was funded by Mind and Life Institute Varela Contemplative Science Research Grant Award No. 09-000107 to Anthony P. Zanesco and Brandon G. King, gifts from the Baumann Foundation and Tan Teo Foundations to Clifford D. Saron

|

Measures:

Continuous performance attention and visual threshold procedure: This task is fully described in MacLean et al., 2010. Participants had to distinguish briefly presented long lines from slightly shorter lines. The length of the shorter lines was gradually increased or decreased until participants could tell long from short about 75% of the time.

Sustained response inhibition task: This task is fully described in Zanesco et al., 2013. Similar to the task above, participants had to distinguish long from short lines after reaching threshold. They then did a 32 minute continuous performance task (without interruption) where they had to press a button every time they saw a long line (about 90% of the time). They were instructed to withhold button presses when they perceived a shorter “target” line (about 10% of the time). This task is designed as a measure of the ability to withhold habitual responses—there were almost 1000 stimuli presented in the 32 min. See also Sahdra et al., 2011.

Mind-wandering while reading task: This task is described in Zanesco et al., 2016. This task was based on a task by Jonathan Schooler’s lab that depended upon gibberish detection. Participants read children’s stories presented one word at a time. As the narrative unfolded (say a story about a trip to the circus) the words would sometimes stop making sense and literally become gibberish. The participant was instructed to press a key as soon as they detected the gibberish. The number of nonsensical words read before detecting gibberish was our measure of mindwandering. At instances of gibberish detection as well as other random times participants were queried as to whether they had “tuned out” (paying minimal attention) or had “zoned out” (were completely distracted) or were on target while reading.

Visuospatial working memory task: This task was based on a task by Luck and Vogel, in which participants view two arrays of differently-colored squares, one after the other. Varying numbers of colored squares (2, 4, 6, or 8) were briefly presented on a computer screen. After a short period the display was repeated. On 50% of trials one of the squares had changed colors. Participants were required to report if the two presentations differed.

Implicit association task (IAT; implicit self-esteem): This task was based on the methods described at Project Implicit in which words are categorized as good or bad when paired in the presence of other stimuli. This IAT was centered on self-descriptors relevant to a person’s sense of self-esteem and self-concept (e.g., I, me, mine).

Affective priming judgment task of subtle emotional expressions: In this task, participants interpreted feeling states from subtle emotional facial expressions. They saw either very subtle positive (happy), very subtle negative (disgust), or objectively neutral facial expressions presented briefly (half a second). As fast as possible, participants were asked to indicate whether the face was expressing positive feelings, negative feelings, or no feelings at all (neutrality). On each trial, these target faces were preceded by an emotional prime—a face expressing either strong happiness, strong disgust, or neutrality.

Self-report measures: 1) the Experiences in Close Relationships scale (attachment; Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998); 2) the Nonattachment Scale (Sahdra, Shaver, & Brown, 2010); 3) the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs, 1983); 4) the Ego-resiliency Scale (Block & Kremen, 1996); 5) Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1979); 6) Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (Brown & Ryan, 2003); 7) Psychological Well-being (Ryff, 1989); 8) Self-compassion Scale (Neff, 2003); 9) Big Five Inventory (John, Donahue, & Kentle, 1991; John & Srivastava, 1999); 10) Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995); 11) Ruminative Response Scale (Treynor, Gonzalez, & Nolen-Hoeksema; 2003); 12) Difficulties in Emotion Regulation (Gratz & Roemer, 2004).

Findings: In the response inhibition task, we found that participants were better at withholding their responses to the short lines after training than they had been before the training. Specifically, they were better able to distinguish the short lines from the long lines and were able to stop themselves from responding when they noticed a rare short line. Importantly, performance did not decline as much over the 30-minute task as it had prior to training, suggesting that the experience of the month-long meditation retreat better equipped participants to sustain attention over time. When we examined the speed of their mouse clicks, we also found that participants were much steadier and consistent following training. These findings confirmed the personal experiences related by the meditators, who reported that they felt more focused during the test. In contrast, the performance of the control group did not change during the period between testing. These findings are described in Zanesco et al., 2013. In this study, we also found that training participants were better able to detect gibberish during reading after the retreat, as described in Zanesco et al. 2016. Finally, after retreat training, participants were more accurate at detecting subtle positive emotional expressions (but not subtle negative expressions), as compared to control participants. Retreat participants were also less likely to incur cognitive costs (reaction time slowing) when processing strong positive emotional primes.

Continuous performance attention and visual threshold procedure: This task is fully described in MacLean et al., 2010. Participants had to distinguish briefly presented long lines from slightly shorter lines. The length of the shorter lines was gradually increased or decreased until participants could tell long from short about 75% of the time.

Sustained response inhibition task: This task is fully described in Zanesco et al., 2013. Similar to the task above, participants had to distinguish long from short lines after reaching threshold. They then did a 32 minute continuous performance task (without interruption) where they had to press a button every time they saw a long line (about 90% of the time). They were instructed to withhold button presses when they perceived a shorter “target” line (about 10% of the time). This task is designed as a measure of the ability to withhold habitual responses—there were almost 1000 stimuli presented in the 32 min. See also Sahdra et al., 2011.

Mind-wandering while reading task: This task is described in Zanesco et al., 2016. This task was based on a task by Jonathan Schooler’s lab that depended upon gibberish detection. Participants read children’s stories presented one word at a time. As the narrative unfolded (say a story about a trip to the circus) the words would sometimes stop making sense and literally become gibberish. The participant was instructed to press a key as soon as they detected the gibberish. The number of nonsensical words read before detecting gibberish was our measure of mindwandering. At instances of gibberish detection as well as other random times participants were queried as to whether they had “tuned out” (paying minimal attention) or had “zoned out” (were completely distracted) or were on target while reading.

Visuospatial working memory task: This task was based on a task by Luck and Vogel, in which participants view two arrays of differently-colored squares, one after the other. Varying numbers of colored squares (2, 4, 6, or 8) were briefly presented on a computer screen. After a short period the display was repeated. On 50% of trials one of the squares had changed colors. Participants were required to report if the two presentations differed.

Implicit association task (IAT; implicit self-esteem): This task was based on the methods described at Project Implicit in which words are categorized as good or bad when paired in the presence of other stimuli. This IAT was centered on self-descriptors relevant to a person’s sense of self-esteem and self-concept (e.g., I, me, mine).

Affective priming judgment task of subtle emotional expressions: In this task, participants interpreted feeling states from subtle emotional facial expressions. They saw either very subtle positive (happy), very subtle negative (disgust), or objectively neutral facial expressions presented briefly (half a second). As fast as possible, participants were asked to indicate whether the face was expressing positive feelings, negative feelings, or no feelings at all (neutrality). On each trial, these target faces were preceded by an emotional prime—a face expressing either strong happiness, strong disgust, or neutrality.

Self-report measures: 1) the Experiences in Close Relationships scale (attachment; Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998); 2) the Nonattachment Scale (Sahdra, Shaver, & Brown, 2010); 3) the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs, 1983); 4) the Ego-resiliency Scale (Block & Kremen, 1996); 5) Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1979); 6) Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (Brown & Ryan, 2003); 7) Psychological Well-being (Ryff, 1989); 8) Self-compassion Scale (Neff, 2003); 9) Big Five Inventory (John, Donahue, & Kentle, 1991; John & Srivastava, 1999); 10) Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995); 11) Ruminative Response Scale (Treynor, Gonzalez, & Nolen-Hoeksema; 2003); 12) Difficulties in Emotion Regulation (Gratz & Roemer, 2004).

Findings: In the response inhibition task, we found that participants were better at withholding their responses to the short lines after training than they had been before the training. Specifically, they were better able to distinguish the short lines from the long lines and were able to stop themselves from responding when they noticed a rare short line. Importantly, performance did not decline as much over the 30-minute task as it had prior to training, suggesting that the experience of the month-long meditation retreat better equipped participants to sustain attention over time. When we examined the speed of their mouse clicks, we also found that participants were much steadier and consistent following training. These findings confirmed the personal experiences related by the meditators, who reported that they felt more focused during the test. In contrast, the performance of the control group did not change during the period between testing. These findings are described in Zanesco et al., 2013. In this study, we also found that training participants were better able to detect gibberish during reading after the retreat, as described in Zanesco et al. 2016. Finally, after retreat training, participants were more accurate at detecting subtle positive emotional expressions (but not subtle negative expressions), as compared to control participants. Retreat participants were also less likely to incur cognitive costs (reaction time slowing) when processing strong positive emotional primes.

Publications

- Zanesco, A. P., King, B. G., MacLean, K. A., Jacobs, T. L., Aichele, S. R., Wallace, B. A., Smallwood, J., Schooler, J. W., & Saron, C. D. (2016). Meditation training influences mind wandering and mindless reading. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice, 3, 12–33. http://doi.org/10.1037/cns0000082

- Zanesco, A. P., King, B. G., MacLean, K. A., & Saron, C. D. (2013). Executive control and felt concentrative engagement following intensive meditation training. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 566. http://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00566